We wanted to talk about what we learned running 30 million agentic operations monthly in production for companies like Google and DoorDash over the few months.

Because when you operate at that scale, you see something that isn't obvious from the outside: search as a paradigm has reached its limits. Not just for the "deep web," but for the web we thought we'd solved.

This is what we synthesized.

When Search Worked

To understand why this matters, it helps to go back to the original architecture of the web.

In the 1990s, Tim Berners-Lee designed the web around three core concepts: URLs (addresses), HTTP (how to request things), and HTML (how to display things). The genius was in the simplicity that anyone could create a page, link to other pages, and the whole thing just worked.

Search engines emerged because this created a discovery problem. With millions of pages, how do you find what you need? Google's insight was PageRank by using the link structure itself to determine relevance.

This worked because of a fundamental architectural assumption: content on the web was meant to be read by anyone who had the URL. Public by default. Linkable by design.

The Aggregation Opportunity

This web architecture enabled aggregation. Google didn't need permission to crawl websites. They were public. The content was right there in the HTML. All Google had to do was:

The economic logic was elegant. In a world of infinite supply (websites), the scarce resource was demand (users looking for things). Whoever aggregated demand won.

This is why Google's business model works. Users come to Google first. Google sends them to destinations. Destinations pay for visibility. The aggregator captures value.

When Search Stopped Working

But here's what we missed: search didn't just fail to reach the deep web. It started failing on the indexed web too.

Consider Amazon.

Google indexes millions of Amazon product pages. These are public, crawlable URLs - exactly what search was designed for.

And yet when you search Google for "laptop," you get Amazon results... along with 10,000 other results. When you search Amazon's own search for "laptop," you get thousands of pages of results. Sponsored products. Fake reviews. AI-generated descriptions.

You give up and click something "good enough."

The problem isn't that data is hidden. It's that there's too much data for search to be useful.

Google successfully indexed millions of Amazon pages. That didn't help. Amazon built its own search engine for its catalog. That didn't help either.

The web got too big for ranking to work - even for the public, indexed part. Even when a single company controls the entire catalog.

Search assumes you want to FIND something. But what if you need to CHECK everything? Compare ALL options? Verify every supplier?

That's when the paradigm breaks.

The Structural Constraint

And it gets worse, because this is just the 5-10% of the web that search actually indexes.

The remaining 90-95% - the "deep web" - lives behind forms, logins, and interactive interfaces:

Search engines can't aggregate this. Not because they lack the technology, but because the architecture doesn't allow it. You can't crawl what requires interaction to access.

So we have two problems:

Both problems have the same root cause: search as a paradigm assumes a human will manually evaluate results. It breaks when you need comprehensive intelligence, not ranked options.

Why This Matters Now

For most of the internet's history, this constraint was manageable. The readable web was where money got made. News sites, e-commerce, information - all designed to be crawled and indexed. The deep web was back-office systems that enterprises managed internally.

But consider what happened with ClassPass.

ClassPass aggregates fitness classes: Tens of thousands studios, yoga classes, spin studios, massage parlors. Classic aggregation play - control the customer relationship, fragment the suppliers.

Except most of these studios don't have APIs. They have booking websites that get updated manually. Class schedules change daily. Pricing varies by time, location, tier.

For ClassPass to actually know what's available right now, they need to check 30,000 websites. Continuously.

They tried the traditional approaches:

TinyFish increased their venue coverage 3-4x while reducing costs 50%, by navigating the actual booking interfaces the way a human would - except across thousands of sites simultaneously.

This is the structural reality: aggregators can't scale to the edges. Search can't handle comprehensive queries. And the web keeps getting bigger.

The Labor Economics

The constraint isn't just technical. It's economic.

Think about what a procurement team faces. They need competitive pricing across 200 supplier portals. Each portal requires login, has a different interface, different workflow.

You could hire someone to manually check all 200. But the labor cost is prohibitive. So you check 5. Maybe 10. You make decisions based on incomplete data because complete data is economically inaccessible.

Or consider pharmaceutical companies matching patients to clinical trials. Eligibility criteria exist across thousands of fragmented research sites. The data is there. But manually checking it all? Impossible at scale.

The constraint isn't "this is tedious work we'd like to automate." It's "this is analysis we literally cannot do at the volume we need."

This is where TinyFish's 30 million operations number becomes interesting.

The Operational Model

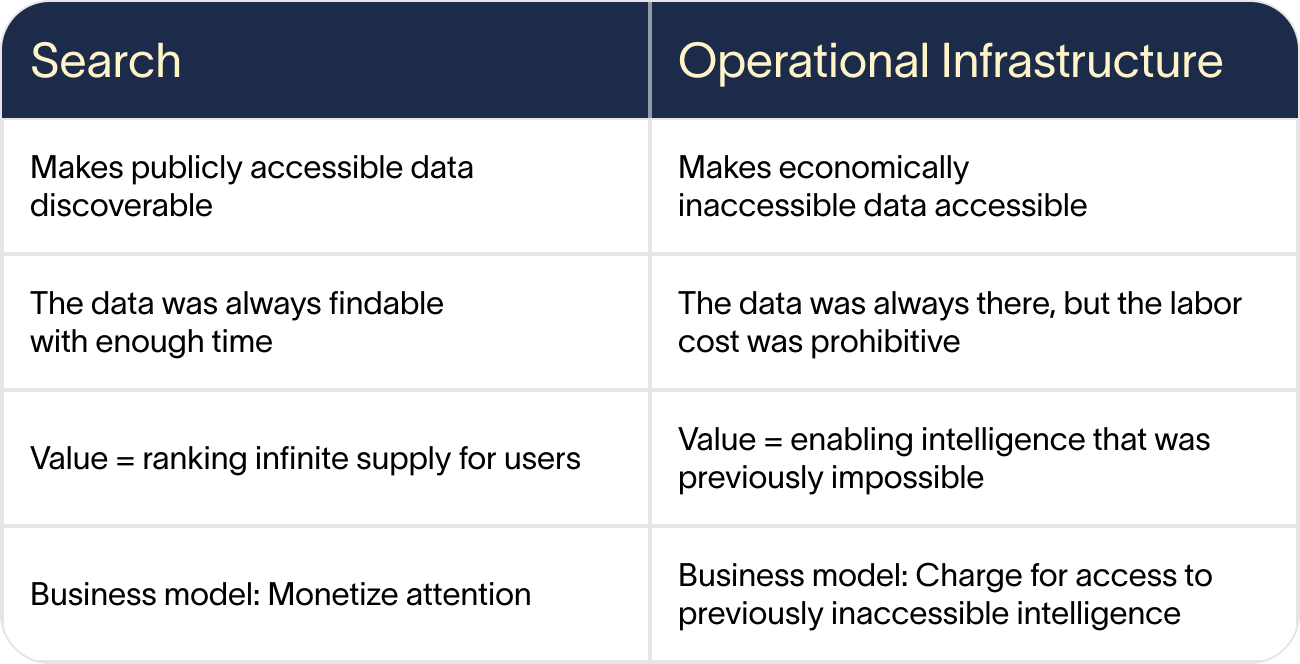

What TinyFish built isn't search infrastructure. It's operational infrastructure.

The agentic system can:

And the economics are fundamentally different from search, because it makes economically inaccessible data accessible.

Search assumed the hard part was finding needles in haystacks. But at least you could look through the haystack if you had time.

Operational infrastructure solves both problems search can't:

Why Browser Agents Don't Solve This

You might think, "Don't browser agents like OpenAI's Atlas do this already?"

They do, but at the wrong scale.

Browser agents operate in user context - one session, one browser, human speed. They're productivity tools. They help you navigate websites faster.

But they don't solve the enterprise problem: reliable intelligence across thousands of fragmented systems. You can't run 30 million operations monthly through a browser agent that operates one session at a time.

It's the difference between a bicycle and a freight network. Both involve transportation, but they solve different problems.

The Infrastructure Play

The path here is clear: this is horizontal infrastructure, not vertical SaaS.

The pattern is consistent. AWS didn't start by building vertical cloud applications for retailers. It exposed compute primitives and let others build. Stripe didn't build vertical payment solutions for SaaS companies. It made payments programmable and let developers integrate.

TinyFish is following the same playbook. Start with the public web - competitive intelligence, market data, compliance monitoring - because it doesn't require credentials or security reviews. Prove the infrastructure works. Build trust.

Then expand to credentialed systems once enterprises see the value and are willing to grant access.

This is the only model that makes sense because the operational web is too fragmented for vertical solutions. Every industry has different portals, different workflows, different authentication patterns. You can't build "healthcare operational navigation" and "retail operational navigation" as separate products. The underlying infrastructure is the same.

What changes is the domain logic - what data to extract, how to validate it, what structure to return. But that's configuration, not infrastructure.

What This Means

Search worked brilliantly for 25 years because the web was small enough for human evaluation of ranked results.

The web got too big. Even the indexed part became unmanageable. And 95% was never indexed at all.

We built TinyFish because we kept running into the same problem: valuable data existed, but accessing it at scale was economically impossible. Not difficult. Impossible.

The paradigm that comes next isn't better search or smarter ranking. It's operational infrastructure that can navigate, reason, and extract across the entire web - public and private, indexed and unindexed.

We're running 30 million operations monthly in production today. For Google, DoorDash, and others who need comprehensive intelligence, not ranked options.

But we're still early. The operational web is massive, and the problems enterprises face are more varied than we initially understood. Which is why we're opening our infrastructure to a selected group of developers this month.

If you're building products that need:

We'd like to work with you.

We believe the best way to build the operational layer of the internet is with the people who have real problems to solve.

The web got too big for search. We're building what replaces it.

Sign up for our beta: